>Final Report by Michael Janis and Tim Tate regarding their Fulbright Specialist Program at the University Of Sunderland and the National Glass Center.

The bonds that were forged years ago when The City of Washington & Washington Glass School hosted the UK artists from Cohesion Glass Network art Artomatic’s Glass 3 event in Georgetown have been strengthened. Our connection with Washington, DC’s UK Sister City, Sunderland, the National Glass Center and the University of Sunderland; will continue throughout our careers. While our mission as Fulbright Scholars was to impart information, we leave having learned many lessons.

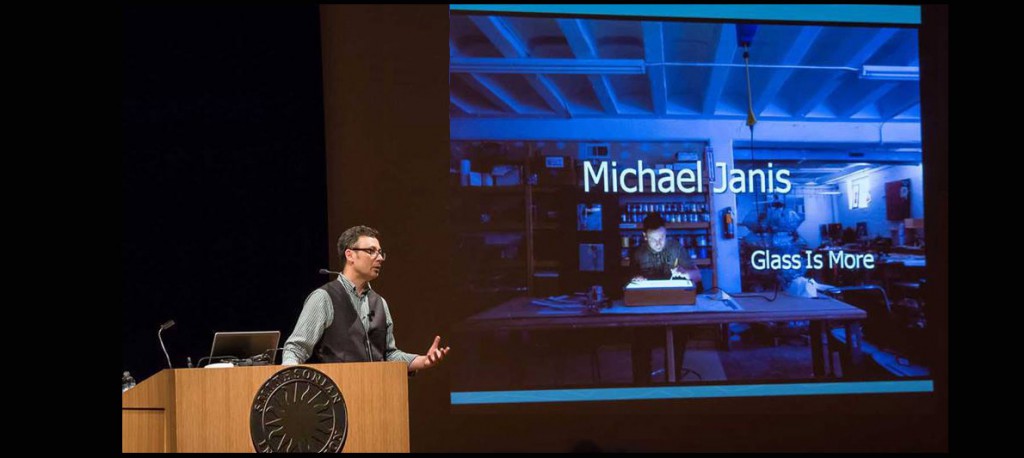

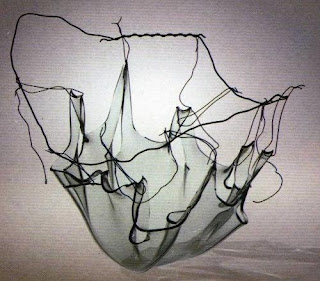

Our time in England began with presentations of our artwork and discussions of on new directions the glass world was embracing, such as Glass Secessionism, where artists are looking to move from the aesthetic of pure technique, materials and process and are advancing glass as a medium of sculptural expression in the narrative realm. The participants in the audiences came from the student body of the University as well as working artists from Sunderland, Newcastle, even as far away as Edinburgh, Scotland. The audience stayed long after the talk, and topics from the discussion continued to come up during our entire Fulbright program stay (and indeed, afterwards via the internet) showing the strong relevance of the concepts.

We created workshops for both the National Glass Center and Sunderland’s Creative Cohesion studio; the city’s artist incubator (that, in fact, used the Washington Glass School as its educational and business model). The City of Sunderland invited us to speak with students at a local secondary school during our stay, where we talked about careers in art. We also worked with the Leaders of the University’s Glass and Ceramics program and outlined methods we could extend the cooperative agreement that exists between Sunderland and Washington, DC.

The British tertiary arts education system is different from the US university model. Their MA program blends an MFA and BFA into a very concentrated program. The amount of expertise, materials and techniques they make available to students seems staggering. Sunderland’s may be the finest glass program in the world. With the National Glass Center, the physical space alone dwarfs any facility in the US (or even if one combined the arts centers of Pilchuck, Penland, Corning into one place). The University of Sunderland also offer a doctorate in glass, which is similar to an MFA, though the focus is research, as this is one of the primary methods for the University to receive funds. At the end of a student’s time at Sunderland University, they have a much broader base of knowledge regarding glass and its parameters. In many ways the educational system in the UK is ahead of the US, especially in how they treat glass sculpturally.

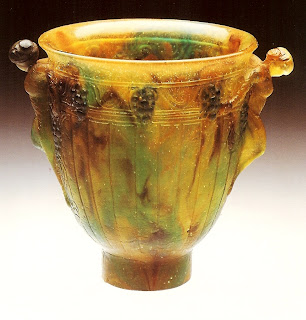

Our talks with the students included observations on the differences between the art practices of the two countries. The gallery/collector focus on technique driven vessels that drove the US Studio Glass Movement for over 40 years did not occur to the same extent in England. Instead of being gallery driven, the UK arts education sector seems to be more exhibition and grant driven. University and museum -sponsored art shows are more common as the way an artist would establish themselves. With this as their foundation, artists do not find it as necessary to focus on a single form. They are able operate with the freedom of each installation being potentially a different medium, voice, direction (though many times I would have liked to see the directions pushed much further.) In the US, with the galleries / collector based system, there exists the perception that an artist’s work be recognized for a particular form and for the work be within a series format.

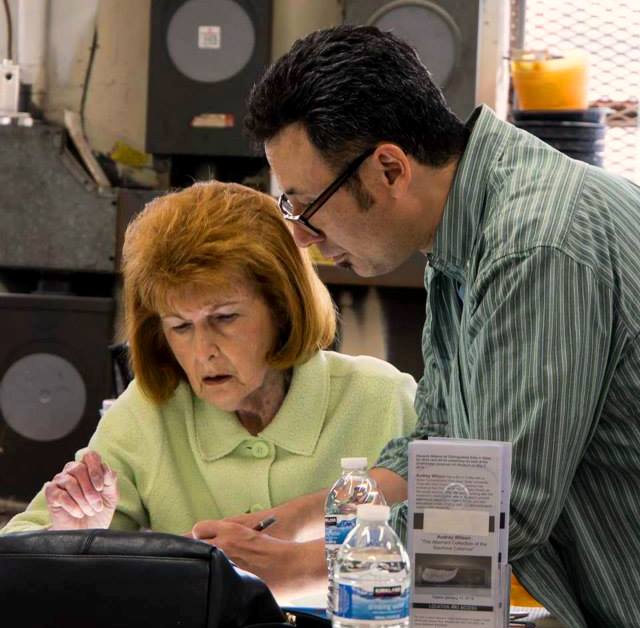

The courses we held at the University included a mix of graduate and undergraduate students, and the workshops allowed and encouraged students working in different modules to interact. We found the students of the University to be some of the most engaged and accomplished students we have ever worked with. They wanted to absorb as much information as possible. Their energy was refreshing, and we added another workshop and added one talk more into the schedule.

Our final discussion was on Artist Covenant’s and how artists can create a network using social media as a way to support each other as a group. This informal talk was packed, standing room only. The artists were voracious in seeking advice on how to get their work seen and recognized. We hope we have helped energize them and perhaps rally them to work together towards their common good. The interest and respect we received from the students was over-whelming. Many of the artists have connected to us online.

We would like to thank all those who made this academic interaction possible: The Fulbright Commission, the Council for International Exchange of Scholars (CIES), The University of Sunderland and the National Glass Center, The City of Sunderland and Creative Cohesion. Each in their own way has made our visit into a life changing experience.

Our mission is to now to reflect and contemplate on not only what we have achieved, but to think of ways on how best to extend our hand and continue our symbiotic and synergistic relationship so that it will not only survive but thrive.

Lets all bridge the Atlantic for many more decades.

Tim Tate & Michael Janis , Co-Directors, Washington Glass School

The final event was the JRA hosted dinner on Sunday evening – it was a very busy exciting weekend for the Washington Glass School!

The final event was the JRA hosted dinner on Sunday evening – it was a very busy exciting weekend for the Washington Glass School!