The Washington Post published the following review of Michael Janis’ solo show “Echoes of Leaves and Shadows” being exhibited at the Maurine Littleton Gallery through Oct 15. Art critic Mark Jenkins describes Michael’s skill as “extraordinary. Jenkins also enthuses that Janis’ glass artwork combines “the stateliness of stained-glass windows with the vivacity of pop art”. Have a read of the full text below:

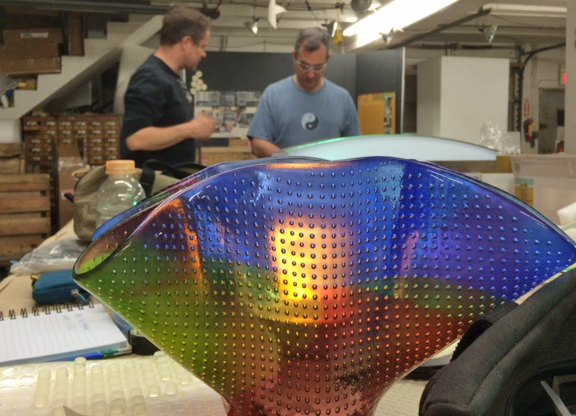

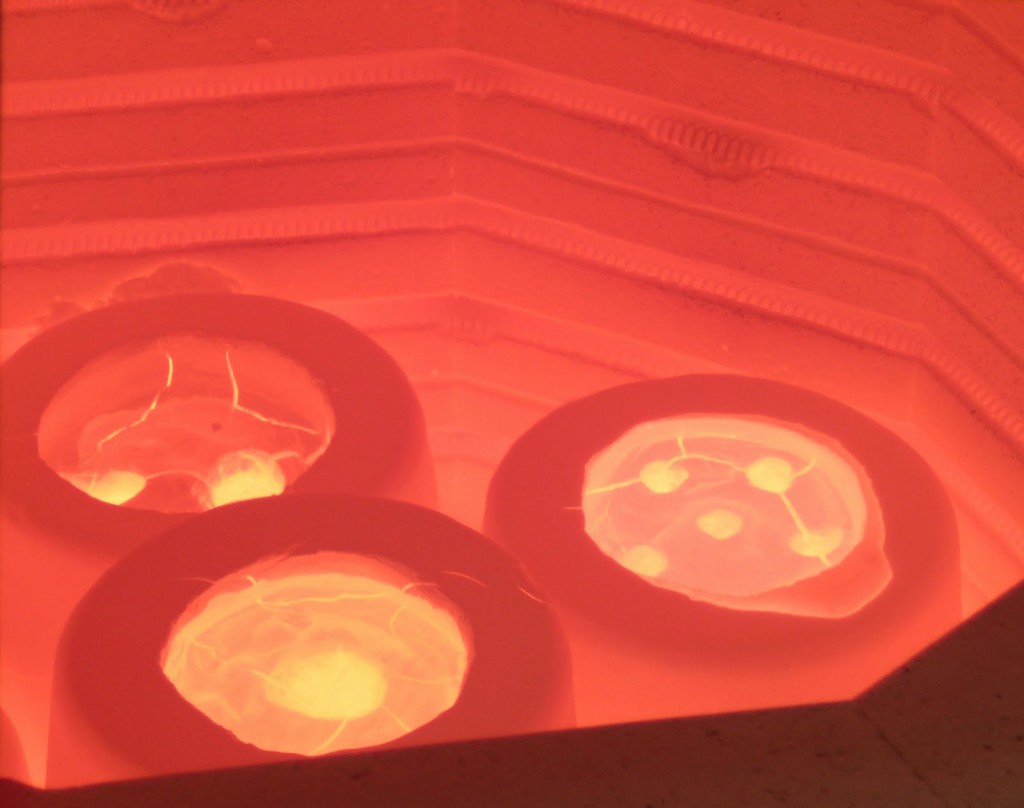

Michael Janis. “Radiance,” 2016, glass, glass powder imagery, steel; on view at Maurine Littleton Gallery. (Michael Janis/Maurine Littleton Gallery)

By Mark Jenkins October 8, 2016

Michael Janis

If Michael Janis worked with pencil or charcoal, his draftsmanship would be impressive. But the D.C. artist draws photorealist portraits with pulverized glass, placing the powder exactly with tiny tools. Which is extraordinary.

Most of the pieces in “Echoes of Leaves and Shadows,” at Maurine Littleton Gallery, include depictions of pretty young women. These gamines, who might be ballerinas or French New Wave stars, are rendered in granulated black glass fused by heat to clear glass sheets. The pieces aren’t just black-and-clear, though. Janis overlays and underlies patches of translucent colored glass, and often adds such 3-D glass elements as butterflies or flower petals. Aqua and orange are common in this array, among other hues. In one picture, an abstract yellow-green swirl contrasts the subject’s slightly darker green eyes.

Janis employs many variations, slicing faces into three equal parts or contrasting them with panels of textured glass. There are ceramic busts garlanded with glass leaves, and portraits embellished with near-opaque peacock- or dark-blue circles. The latter combine the stateliness of stained-glass windows with the vivacity of pop art — half medieval cathedral, half 1960s Vogue.

Michael Janis: Echoes of Leaves and Shadows On view through Oct. 15 at Maurine Littleton Gallery, 1667 Wisconsin Ave. NW. 202-333-9307. littletongallery.com.