April G. Shelford is an intellectual historian that has recently published a new book that seeks to reposition the colonial Atlantic in early modern intellectual history, tracing the advent of particular practices and ideas amongst white male colonists – planters, officials, doctors, merchants, and military men. As described in a review of April’s book by Ingrid Schreiber of the University of Oxford, these “Enlightened” colonists sought to assert their identity as legitimate thinkers and civilized, modern individuals. This was, on the one hand, an attempt to assume a shared culture and gentility with Europeans, and colonists eagerly emulated the fashions of metropolitan consumer culture, including in the amassing of globes, telescopes, and musical instruments. Whether asserting a European or uniquely Caribbean identity, colonists relied on the figure of the enslaved as a symbolic Other to civilization, thus reinforcing a logic of racial superiority. How did these as models of colonial morality and with their sense of noblesse oblige reconcile the realities all the while maintaining a notoriety for cruelty toward the slaves on their own properties? April’s new book brings to life some all-too forgotten corners of Caribbean history.

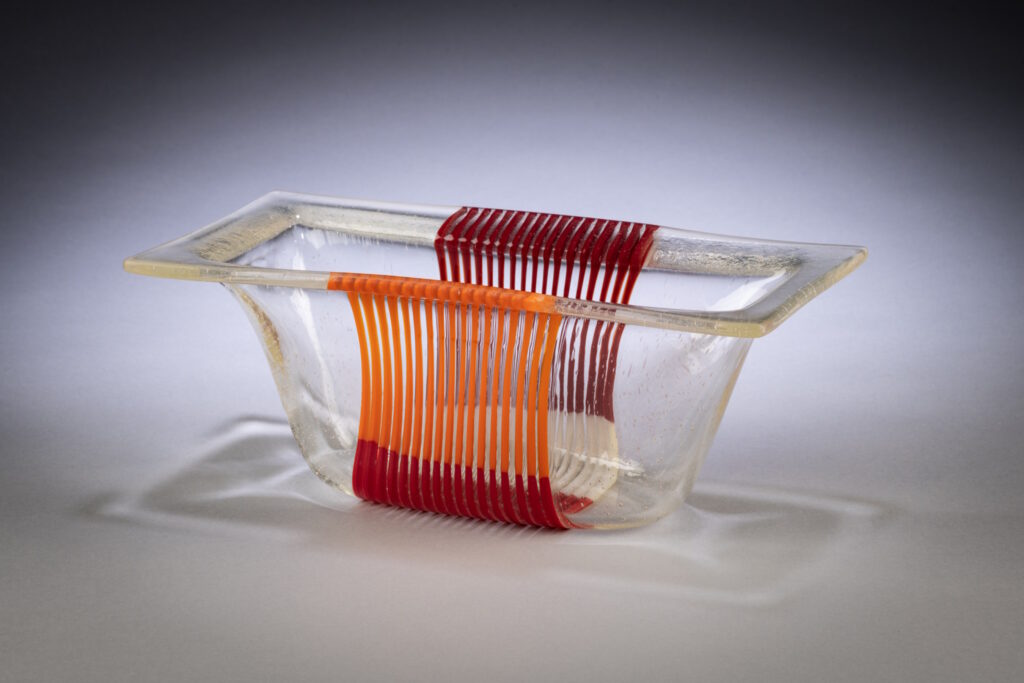

April is also one of the Washington Glass School Faculty and Resident Artist, and she recently had a solo exhibit of her glass sculptures at the Brentwood Arts “Front Window Gallery”.

We caught up with the multitalented artist and historian April a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

What inspired you to delve into the intellectual life of the Caribbean during the 18th century?

As we historians like to say, it was all contingent. About 25 years ago, I’d been on the academic job market for a while & couldn’t get a position. (Since then, the situation for new phds has become just dire.) A colleague heard about a two-year position at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, & he & another colleague went to bat for me. So I was hired to teach European history, mostly early modern (roughly 1450-1789). I trained in 17th-century France–the “Great Century” of Louis XIV–& here I was in a former British colony built on the foundation of very profitable agricultural commodities (chiefly sugar) w/a labor force of thousands & thousands of enslaved Africans. I knew nothing about this history, & a colleague at UWI suggested I “look around” & see whether I could find topics to research. The rest, as they say, is history, if not in a straight line!

How do you hope your book contributes to our understanding of intellectual history in colonial Caribbean worlds?

When I first began working on the eighteenth-century Caribbean, the dominant view in a sense was that there was no intellectual history to tell. Then & now, the image of White Caribbean societies was that they were utterly philistine. That view was increasingly changing among scholars as I was researching this book. And please note: the cliche of philistinism was like all cliches–there’s always a tough kernel of truth. But some early research convinced me that that wasn’t the whole story, & that this other part was worth telling.

When most people think of Enlightenment, they think of Voltaire, Adam Smith, in North America, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin. There are a couple of prominent Caribbean intellectuals, French & British. But I was doing something different. For a long time, scholars have been rethinking Enlightenment; the result is studying how Enlightenment ideas spread & most importantly how people used them to understand the world they lived in, developed & extended them to change their situations. And that was the point: acquiring “useful” knowledge to “improve” some aspects of personal and social life.

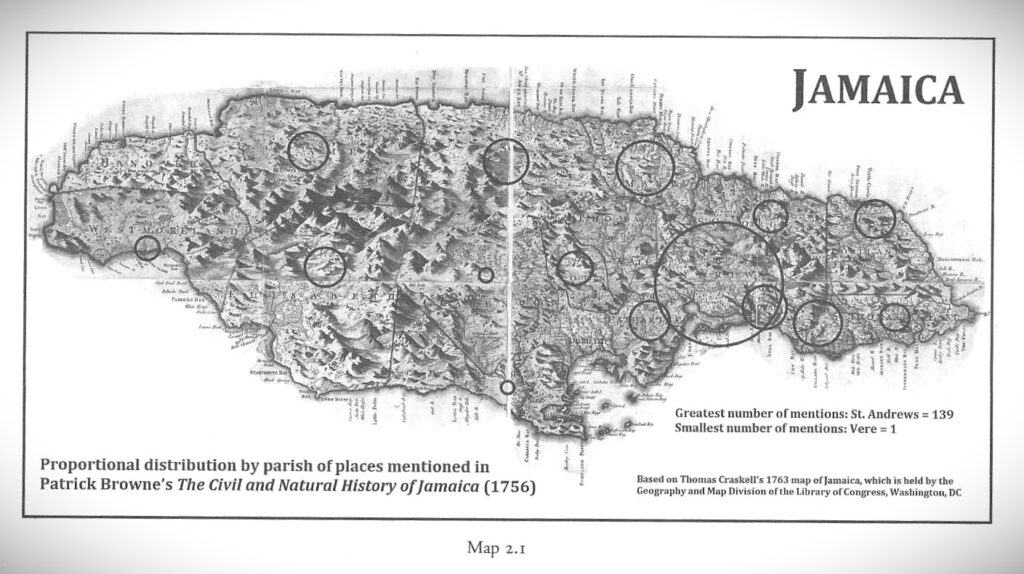

Some examples: When a lot of Americans think about Enlightenment, they think about politics, rights & their foundation. And you certainly see that in the Caribbean. When the editor of a newspaper in Saint Domingue (now Haiti) published many articles on the Stamp Act crisis in North America, he was giving to French colonial readers more ideas about defining their rights vs the French government–& believe me, they were no happier with their colonial governors than colonists in Virginia or Massachusetts. But the Enlightenment was also–maybe even more on both sides of the Atlantic–about agricultural improvement. So you had French colonists writing into the newspaper about improving the cultivation & processing of existing crops, consulting books on botany & chemistry, sending information to metropolitan scientific societies. Publications were most important in spreading Enlightenment ideas, so I spend a lot of time in two chapters giving a sense of how many books were coming into Jamaica, what kind, how people shared them & what they might have made of them.

As these were slave societies, as this was a period during which ideas of equality AND race were developing, & as anti-slavery feeling was emerging later in the century–well, it all bubbles up in the sources. French colonists wrote planters manuals, some of which get into questions of managing the enslaved. Assumptions about the “nature” of the enslaved, their capacities, some explicit, some implicit undergird the authors’ discussions. An overseer in British Jamaica read through a lot of material on slavery & the enslaved, practical advice & “scientific” assertions that we now completely reject. What did he make of all this? Tough to determine from his notes, but his reading exposed him to a lot of ideas, not all of them in agreement.

One of the things I think is most valuable about my study is showing how Enlightenment could contribute to the making of a White colonial identity, a “politics of culture,” as an American colonial historian once put it. Becoming “enlightened,” if you will, was a way for colonists to push back against metropolitan characterizations of them as degenerate Philistines. It was also a way to assert that their authority over the enslaved was not just a matter of brute strength & violence– the Caribbean was a place of terrifying violence– but that it was also legitimated by cultural superiority.

As a glass artist and author, do you find any parallels or connections between your artistic process and the historical narratives you explore in your book?

During a lot of the period of researching & writing this book, I was getting into glass, & I thought that these were just different. But there are similarities. As a historian, I’m really source driven. I read an eighteenth-century book, & I wonder, why did this person think this way? Who were they? Who were they talking to? What did their readers make of it? So when I start, I’m not at all clear how it’s going to come out, what story I’m telling, what else I need to know, what my work might contribute to historical debates. Eventually, I get there. Glass is THE source, & more often than not I don’t know what I might be getting at with it. Most of my work is based on slicing up bigger pieces into smaller, then assembling them in a way that makes sense. Writing history, I’m always assembling bits and pieces into something that (I hope!) means something, that I feel I’ve responsibly interpreted. Then you open the kiln door & get something you didn’t expect, so you have to rethink, sometimes dump it. Believe me, when I write, a lot ends up on the cutting room floor (sorry for the mixed metaphors!). Writing & glass-making are both processes, & you have to trust the process.

You are quickly rising in the glass art world – do you see any parallels in the academic world and the art world?

First, please, I don’t see myself as rising in the glass art world, though I’m flattered you think so. But I can say something about parallels. I see history as a humanities subject first & foremost. These are called disciplines because it takes a lot to learn your craft. The humanities are about human beings, & human beings are terrifyingly complicated, so we’ll be wrangling about what it means to be human forever. That doesn’t make the question less important–if anything it makes it more central to what we think we should do as individuals, as a society, even as a world. And with AI coming on strong, we might want to get to work on it yesterday. What more basic question than the meaning of being human is there in art? And you have to learn your craft, your discipline–you have to work at it. But there’s joy in the work, historical, artistic. Unfortunately both endeavors are horribly undervalued, & it seems to get worse & worse. We all know about art programs & humanities departments being cut back, even closed. This diminishes all of us, every one of us, as human beings.

Tell us about your next project. Is there a new book in the works? Perhaps a glass mystery?!

No idea. I have some much more modest historical writing projects in mind. I’m currently involved in an editorial project with an academic journal, & I’m loving it. With glass, I want to push myself to go bigger & learn some new techniques. I’d like to explore photo transfer: In my mind, I see a big book–now there’s crossover! I also feel I can say more. Making something that’s aesthetically pleasing–that’s enough. But I love it when someone feels a piece speaks to them.

Follow April on Instagram: April Shelford (@aprilglassshelford)