>

élan magazine, the Northern Virginia publication about artists has a great profile on WGS artist Michael Janis. Written by Polly Nell Jones, the article delves into Michael’s influences and inspirations. The color quality of the images is amazing – below is the text from the magazine:

Layered Stories

The Magic of Everyday Life

By Polly Nell Jones

élan magazine, July 2011/ page 40-43

At first glance, the pensive portraits, whimsical botanicals and delicate architectural structures might appear to be acrylic layered with a polymer or watercolor or even pen etchings covered in glass. For many viewers, the intricacies of the glass medium are secondary to the sensitive and somewhat provocative impressions: a raven’s head atop a female body, a teasing collage featuring a manila folder reading, “other side first” or an ironic 19th-century lady titled “Somewhere I Have Never Traveled.” Whether creating the figurative or the surreal, glass artist Michael Janis is a storyteller, a promoter of symbolism and a connector to interior worlds.

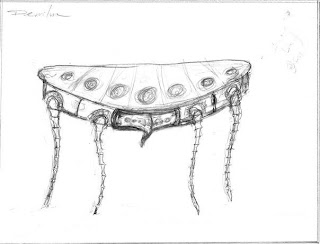

After making a rough initial sketch to achieve a sense of scale and proportion, Michael creates an image on a Bullseye glass slab, working sgraffito-style with a fine silica-based frit. He begins by spreading the frit onto a glass surface and then sketches an image using an X-ACTO knife and a synthetic brush to reveal the desired result.

To attain delicacy and depth in his detailed assemblages, Michael employs multiple firings to stabilize each section of a piece. He also creates additional plates, layering them experimentally until he is satisfied with backgrounds, sometimes blocking out an opaque section with enamel paint. A final firing fuses all the plates together, as many as six for some pieces, and when he is finished, his images seem to float within the glass.

“I say I collaborate with glass,” says Michael, “but glass is the master. When I close the kiln door, I always do my glass mojo dance.” Kiln schedules are computer-regulated, but Michael is still able to achieve innovative results through annealing or graduated temperature reductions. Vagaries in the layering process can lead to unexpected air bubbles that are mostly appreciated.

Born in Chicago and the youngest of three brothers, Michael is a study in diversity. His father was Greek-German, and his mother was of Filipino-Chinese-Spanish descent. “I was the odd one,” he says. “I wanted to do the art stuff. That’s why I studied architecture, but then I discovered that it’s not art.”

He reflects on his time at the Illinois Institute of Technology and the architectural program designed by Mies van der Rohe, it was there that Michael learned from a tradition predating computer-generated design programs – a tradition that emphasized the basics of drafting beginning with how to shave a pencil point. Michael acknowledges that the rigorous training gave him the skills he continues to use to lay out and design his constructions.

For 10 years, Michael and his architect wife Kay lived in Australia. While there, he began to work with art glass installation. Returning stateside in 2003, the couple ended up in Washington, D.C., with Michael determined to work with glass full time.

While Kay supported him, he experimented with glassblowing, worked with Jeremy Lepisto, president of the Glass Art Society, on kiln-fired imagery. Eventually he took a class at the Washington Glass School in Mount Rainier, Maryland, becoming the self-described “shop monkey,” cleaning up after classes, watching various projects progress and learning about the behavior of glass under fire. He worked on engraving and image transfer but yearned to go larger, which led him to what he refers to as “pushing powder.”

At the Washington Glass School, where Michael is now a co-director in charge of public art and architecture, his desk is piled with papers helter skelter, not at all in keeping with the precision and detail of his work. Several weeks before a show, he shrugs, chuckling at the prospect of looming deadlines, including one for a site-specific eight-foot sculpture made up of seven panels hanging within a freestanding metal frame.

Showing a work in progress for his solo exhibit, A Lighter Hand, at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, Massachusetts, he explains that his architecture training allows him to work with a composition from any angle.

“I was often working upside down on drawings because another architect was working on the drawing on the other side,” he says, comparing the process of manipulating the frit to creating sand painting. Though it seems obvious that walking in front of a fan while moving a piece of art with loose frit to the kiln is not a good idea, Michael finds that students still need to be reminded of such risks.

While working with other artists at the Washington Glass School, he often collaborates on large-scale commission projects that come to the for-profit studio. With his design background, Michael is a natural for making presentation to architectural committees – the difference is that he doesn’t have to wear a suit because now he’s the artist.

Michael’s portrait of his mother includes a map of Manila, timepieces and drafting sketches. Robert Rauschenberg’s collages and Dadaist influences sometimes informs his work. He says he likes viewers to draw their conclusions about meanings. However, he does admit that poetry, symbolism and the magic of everyday life are guides he follows by scratching the surface to plumb the proverbial riddle of life.

“The Memory of Orchids” 12.5″ x 12.5″ fused glass powder

During last month’s GlassWeekend show at the biennial International Symposium and Exhibition of Contemporary Glass in Millville, New Jersey, Michael was designated as “Rising Star.” It is only one in a growing list of awards for Michael, who has been tapped for a Fulbright Teaching Scholarship that he hopes to complete at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland, England. In 2010, he received the California Bay Area Institute Saxe Fellowship, and he was named Outstanding Emerging Artists by the Florida Glass Art Alliance in 2009. Michael is represented by Maurine Littleton Gallery in Washington, D.C.