>How the Washington Glass School is Tied to the War of 1812, The Brits Sacking the White House & The Star Spangled Banner.

|

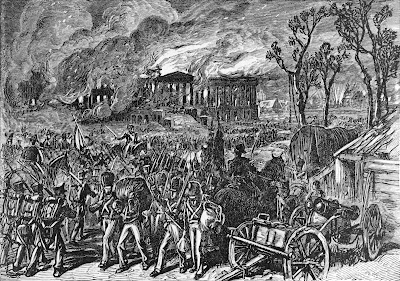

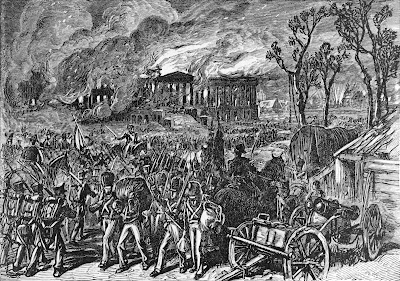

| The British burn the President’s Mansion 1814 |

One of the beauties of being in Washington, DC is the sense of history that surrounds the place. Growing up in northwest suburban Chicago, history seemed to have started after WWII, with suburban subdivisions overtaking farmland. Here, the area is so steeped with the history that appears in grade school books, that important – but deemed lesser – sites can be forgotten; the scurf of yesterdays. As the Maryland area celebrates the Bicentennial of the War of 1812, it is interesting to note that the Washington Glass School building sits atop an important battlefield – one of the key parts in the Battle of Bladensburg. With the US loss at this battle, British forces swept into Capitol Hill and burned the White House, the Capitol and the Treasury.

Since there are no signs on the site – this blog will act as a virtual ‘historical marker”.

Historical Overview

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the United States of America and the British Empire. In these battles, the British set off their new weapon – the Congreve rocket – a rocket carrying about one pound of powder that could travel almost 1,000 yards and their success had a tremendous impact on modern warfare.

After the defeat and exile of Napoleon in April 1814, the British were able to send newly available troops and ships to the war with the United States. On August 20, 1814, over 4,500 seasoned British troops landed at the little town of Benedict, MD and marched fifty miles towards Capitol Hill.

|

Artists Rendering of the Battle of Bladensburg

(Gerry Embleton-Courtesy NPS/Star Spangled Banner National Historic Trail) |

What Went Wrong

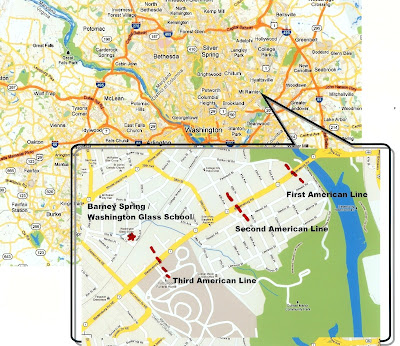

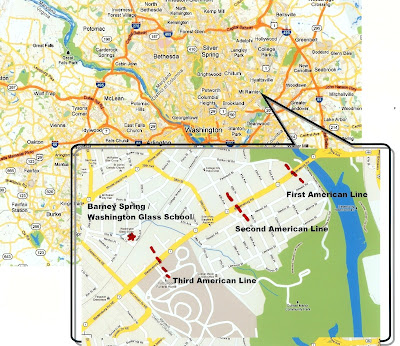

Incorrect deductions that were drawn gave the Americans the impression that Baltimore was their destination. General Armstrong could not be convinced that Washington would be the target of the invasion and not Baltimore, an important center of commerce. There was much confusion trying to outguess the British. In Bladensburg, MD, American troops began to be assembled by Brigadier General William Winder, the Secretary of War, John Armstrong, as well as the Secretary of State, James Monroe. General Smith, another American commander, used his aide – Francis Scott Key – to assemble his troops. Calvary units were positioned to the right of the main road (now called Bladensburg Ave.), while the first and second American lines were positioned nearly a 1/2 mile apart from each other. The organization (and constant second guessing by commanders) of the troops, the general concern about the size of the British army, and the lack of preparation by the rag-tag militia would eventually lead to the undoing of the hastily assembled group.

|

| Current day map showing US troop positions in Battle of Bladensburg |

As the British entered the town, they were greeted by the American troops firing the first volleys across the Eastern Branch of the Potomac (now called Anacostia River). The British initially fell back and moved behind the masonry buildings in Bladensburg. Soon though, the British set off their new weapon – the Congreve rocket. These rockets would eventually become the famous “rocket’s red glare.” British troops began to return fire as the rockets burst above the Americans. American leaders on the first line, unclear on their support from the second line, ordered retreat. American soldiers began to fall back and leave the field via the Georgetown Pike (now Bunker Hill Road). The second line, (positioned approximately at the modern 40th – 38th Avenue) and the members of the Cabinet left the field of battle at or before this point. Cannons were left behind, soldiers moved in haphazard movements responding to the need to fight and the orders for retreat. General chaos reigned across the field of battle.

The strongest attack against the British was made by Commodore Joshua Barney and his seasoned Floatillamen. At Dueling Creek, Kramer’s Militia (troops from Montgomery and Prince George’s County) fought hard against the British but eventually retreated up the hill past Commodore Barney’s men. Barney’s men were valiant fighters, however, the authorities in Washington “forgot” Barney for several days. Without orders, he and his men arrived in the midst of the battle. Combined with Captain Miller’s Marines, Barney fired down the hill toward the British, causing significant British casualties. British troops were ordered into a single file line, flanking Barney’s troop placement and overtaking them. Commodore Barney, after having had his horse killed under him in battle, was severely wounded by a musket ball “near a living fountain of water on the estate of the late Mr. Rives, which was later known as Barney’s Spring“Benson Lossing, Field-book of the War 0f 1812, Chapter 39, 1869

General Winder ordered a general retreat. The retreat order was never passed to Barney’s command, but with no ammunition, flanked on the right and deserted on the left, the Commodore knew that the end had come. He ordered the guns spiked and the men to retreat. The officers and men who were able to march effected the retreat; but the Commodore’s wound rendered him unable to move, and he was made prisoner. He died shortly after; but not before he was able to have influence on Francis Scott Key in his efforts to compose the Star Spangled Banner.

The building that houses the Washington Glass School is located on the site (now near the intersection of Oak and Otis Street).

|

Then & Today

Left inset: Engraving (ca. 1860) of battlefield site where Joshua Barney fell by Benson Lossing in “Field Book of the War of 1812 “ ; Right: Washington Glass School on the same site. Over the past 200 years, the topography has been modified and changed tremendously – the creek now flows under the concrete pathway opposite the Glass School. |

Immediately after the battle, the British sent an advance guard of soldiers to Capitol Hill. The President’s house was burned, and the British raised their Union Flag over Washington.

|

| The Brits pillage the White House. |

The First Lady Dolley Madison remained behind to organize the slaves and staff to save valuables from the British. The buildings housing the Senate and House of Representatives were set ablaze not long after. The interiors of both buildings, which held the Library of Congress, were destroyed, although their thick walls and a torrential rainfall that was caused by a hurricane the following day preserved the exteriors.

|

| During the war of 1812 when the British attacked Washington DC, The First Lady, Dolley Madison stayed behind in the White House to save the artifacts and symbols of America. The engraving above shows her saving the Declaration of Independence. |

With their mission accomplished, the British feared the Americans would reassemble their forces and attack while they were in the vulnerable position of being a long distance from their fleet. The men were miserable in the sweltering temperatures. They were tired, ill and wounded. At dusk the troops quietly withdrew from the city. The troops were so exhausted that many died of fatigue on the four day march back to the ships, several deserted, but the body of men marched on.

Several of the British stragglers and deserters were arrested by citizens in Maryland. When the British commanders learned of the incident, they sent a small force back to arrest William Beanes, a well respected doctor and town elder. Following his arrest, Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key and U.S. Agent for Prisoner Exchange John S. Skinner went to secure Bean’s release from the British. They brought with them letters from British troops who testified as to the compassion that they received while in Bladensburg after the battle. Brought on board one of the British vessels, Francis Scott Key would see the battle in Baltimore raging on and the flag standing at the end of the battle, leading to the writing of the Star Spangled Banner.

Times have changed, and we now rely on the Brits as an important and trusted ally – however -the next time representatives from DC Sister City – Sunderland, England comes for a visit to the Glass School, they have some ‘splaining to do.

For more info – check out the book A Travel Guide to the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake

And also – a link to website that shows the archaeology of the Bladensburg battle site.

This entry was posted in barney's spring, battle of bladensburg, bicentennial, congreve rocket, dolley Madison, francis scott key, joshua barney, rives, star spangled banner, war 1812 by Michael Janis. Bookmark the permalink.