>Nicolas Bell, Curator of the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery talked about the rise of “Sloppy Craft Movement” during his talk on influences of the 40 under 40 exhibit (currently on exhibit thru Feb 3rd 2013). This concept has been talked about in the Glass School for a while, as many of the artists here come from diverse backgrounds – often from outside the glass craft world… and it is a great subject that deserves more attention in the art blogdom world.

“Sloppy Craft” – is this an oxymoron? I thought that many may not understand the concept of sloppy craft, and a cynically-minded person, could view much of the work – often designed to maximize the shock value – as a transparent bid for attention in the contemporary art world, which has long made a point of embracing my-kid-could-do-that aesthetics.

|

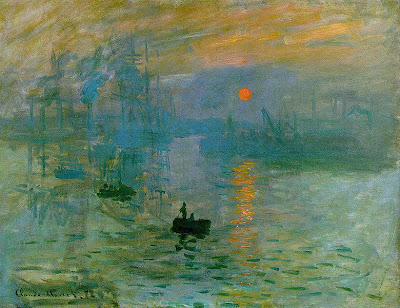

| Mixed Media/Glass sculpture by the De La Torre Brothers Einar and Jamex De La Torre derive their gutsy imagery from such diverse influences as Jose Posada, television, the Vatican and the darling of modern comics, the huge eyed Anime characters. |

In 2009, Glen Adamson, the Deputy Director of Research at the Victoria and Albert Museum coined the phrase “Sloppy Craft” which he defined it as “the unkempt product of a post-disciplinary craft education.”

The origins of “Post Disciplinary Craft” begin in the early 2000’s when new ways of thinking about craft began to form and many saw a need for a more relevant understanding of current craft practice and objects. The earlier models of understanding craft, which relied on either the Arts and Crafts Movement or the Back to the Land counterculture movement that had influenced studio craft in the 1960s and 1970s, would have to be replaced.

The youngsters of craft no longer felt connected to the past – or rather, are not referencing the history of the mediums – that is not their focus. They didn’t learn in apprenticeships with masters and a growing number had abandoned classrooms. They weren’t wed to techniques or materials. University art programs found that the students did not want to be categorized as “glass artists” or “clay artists” and, as the students just want the media skills as part of their repertoire, sought to merge curriculums under the term “Material Studies”. Young crafters also learned from other sources – such as their peers or the Internet. The digital age would be to craft what the sexual revolution was to feminism. This is an approach to craft that resonates with the times, linking craft to the wider concerns of today’s society (ie: think global,act local; feminism; gender politics; social justice and ecological concerns). The don’t be precious DYI movementresponse of current craft students were a couple of other aspects of “sloppy craft.” One was the recycling of materials — found or “trash” art, one might call it. It’s everywhere these days, certainly if you looked at the works at DC’s semi-annual artfest Artomatic – and no one bats an eye at the exhibits. The other aspect of this kind of casual crafting is that it appears most often in assemblages and collage. Assemblages and collage have clear ancestors, dating back to Picasso through Rauschenberg and are seen and made by thousands of people who may not even think of themselves as artists.

Traditionally, a craftsperson would spend years polishing their craft, working at the highest level until one was so good that one could let it go – forgetting technique and working from the heart intuitively; the crafter/artist would have behind them all the knowledge needed to return to “fineness” if the artwork required it.

To some extent Josh Faught fits that mold. He self-identified as a Fibers Major at the Art Institute of

|

| Einar and Jamex de la Torre |

But making things, it turns out, is still quite difficult. Indeed, the one thing that seems to bind the majority of contemporary art together is the lack of skill required to create it. Glen Adamson also explored the popular notion of what defines “craft” and why some may think that craft always has to be finely made. He states,” On the one hand, skill commands respect. We value the integrity of the well-made object, the time and care it demands. Therefore, what we most want out of our craft is something like perfection. On the other hand, though, we value craft’s irregularity– it’s human, indeed humane, character. We want craft to stand in opposition to the slick and soulless products of systematized industrial production.” With this in mind many people would want to consider something very well made to be craft and not something considered to be sloppy craft.

What about the name of the movement – “sloppy craft”? “Sloppy” is really a sound bite kind of name, irresistible once spoken out loud. The reference was used extensively with textile and fabric art, but examples can be found in all the crafts. “Sloppy” indicates intentionality, which might not be the case with the art. “Sloppy Craft” is an unfortunate phrase — perhaps other names like “informal” “casual” or “raw” would be less jarring than “sloppy” to describe contemporary art that has some base in traditional crafts.

Artists need to examine these historical approaches and goals –whether it is humility, authenticity, expressiveness, shock value and impact – to see if they are useful in understanding and contextualizing sloppy and post-disciplinary craft. At the very least, it will help demonstrate whether contemporary craft is an evolution (of its prior forms) or a revolution.